At the source

At the source

At the source

At the sourceBack in Zaduo, I began a serious search for a jeep and driver to take me further into the Mekong’s headwaters; and an English-speaking Tibetan who had befriended me came up with both. A local man called Duojie apparently knew the road to the hamlet of Zaqing and beyond, and after some discussion we agreed on a price for a trip of up to a week by jeep and then possibly horses. In case we couldn’t spend each night with yak herders, he’d bring his own tent.

Rather disconcertingly his name was pronounced ‘Dodgy’, but this was really unfair. He took me out for a sumptuous Tibetan meal on the eve of our departure. I decided I was going to get on well with him.

Next morning we set off at a good early hour, and at the edge of town the road surface ran out. It wouldn’t be a great exaggeration to say so did the road, because for much of the day we were just following tyre tracks. Southern Qinghai is incredibly mountainous so there were lots of passes to cross and rivers to charge through, hoping the jeep wouldn’t stall in mid-flow. After crossing several rivers where the water came in through the doors, we finally reached one that even Duojie wouldn’t attempt; it was just too deep. The light was failing, so we stayed with a nomad family in their big tent, and next morning the father showed us a stretch of river where the water was shallower.

About lunchtime we arrived at Huse Monastery, which must be one of the remotest settlements in the world. It consists of four monks, four lay assistants, some hangers-on and three huge Tibetan guard dogs. What they had to guard wasn’t quite clear, as the monastery was in a gated compound, and they spent most of their time fast asleep.

It was here that we came across Busrr. I’m not sure what he was doing there, as he lived miles away up the valley, but it took him about five seconds to accept the offer that Duojie suggested, £3.20 per horse per day for four horses – one for each of us and one for the tents, bedding and food – and a further £3.20 per day for his services as horseman and guide. In all I eventually paid him £48 and my headtorch, and he was thrilled to bits.

Before we left, I went out for a pee, and it was then that the dog came at me. I didn’t even see it, but turned a corner and Wham! It launched into me so hard it knocked me clean off my feet. Immediately it was all over me, biting the top of one leg and my hands – anything it could get hold of I suppose. I’ll never forget the power of those jaws closing on my little finger – I was sure it had been bitten right off.

Luckily the dog was right at the end of its chain; so I scrambled out of reach and then everyone rushed out to see what the commotion was. I don’t think they’d had much training in first aid – it took me five minutes of shouting and pointing just to get a bowl of cold water. There was blood everywhere, but at last Duojie helped me wash it all away and to my surprise the cuts weren’t so very bad. My fingers were all there. They found some cotton wool and alcohol and dosed everything liberally, then made me drink the little that was left.

My first thought was rabies. I’d had a precautionary jab, but I knew a booster was essential within 24 hours of an infectious bite. Oh well, we were several days’ bumpy journey by jeep, lorry and bus from the provincial capital Xining, the nearest place likely to have any rabies vaccine. I’d just have to hope the dog was healthy.

The chief lay assistant said a funny thing though. “Do you know, exactly the same thing happened to a Chinese man last week. He took off for Xining and we never saw him again.” Different dog, I decided.

The main problem in the nomads’ tents where we stayed was getting water. Tibetans in the countryside don’t wash with water. Even though the camps are surrounded by streams and ponds, they were horrified to see me swishing it over my cuts. There might be a huge cauldron simmering away on the stove, but this was strictly for boiling up yak meat and making yak-butter tea. Even after stripping a carcass or laying out fresh yak dung to dry in the sun, they just wipe their hands with a dry cloth. The trouble was, I wasn’t allowed out on my own because of the dogs; but after much cajoling I usually managed to get a drinking bowl with a little cold water in it. Not surprisingly, the cuts were slow to heal, and I was afraid for a while that they might go septic.

We spent the second night with Busrr’s family in their tent. I was terrified that we’d get no further, because I’d promised Duojie that if my cuts were badly swollen we’d return to Zaduo. But luckily they were no worse than the previous evening, so we set off with the horses on a rather circuitous route, to take in the tent of a Tibetan doctor.

My horse was fantastic – a real plodder – and I must say Duojie and Busrr were pretty good too, constantly adjusting the packs and saddles and making sure I didn’t fall off. Busrr was a true man of the saddle, never happier than when galloping across the grassland, snorting snuff from his gourd and watching his animals graze. But he was also a pure-blooded Khampa, the race that had struck terror into the Chinese during their takeover of Tibet in the 1950s, and he had continued fighting with the Tibetan resistance for another 20 years. He delighted us one afternoon by miming his drill routine, pretend rifle and all, concluding with the spat-out words, “Mao Zedong – shit!”

The Tibetan doctor took me into his tent, inspected me gravely, tut-tutted a lot, then took out some herbal and mineral treatments from a chest of drawers which he ground up between two stones. “Half a teaspoonful twice a day, that'll be 50p please,” he pronounced. No mention of rabies.

The riding was easy across the vast rolling grasslands, and I had time to gaze at the mountains and glaciers getting steadily closer. We stopped for yak-butter tea at a camp where they were in the middle of sheepshearing, using hand-clippers just like in Patagonia. Finally we splashed across a wide river and dismounted at the camp where we were to spend the third night. Out came the yak-butter tea again, followed by bowls of yoghurt, rounds of unleavened bread and great hunks of almost inedible boiled yak-meat.

The hospitality of the Tibetan families in the high grasslands seems boundless. Accommodating and feeding complete strangers comes naturally to them – I never saw any money change hands. Also, unlike Peruvians, they seem devoted to their neighbours and would never dream of stealing their animals. Despite the obvious shortcomings of hygiene and healthcare, I think they’ve managed to create a really very humane society up there and I hope it’ll be strong enough to resist the encroaching Chinese.

The third night was a disaster for the family and for us. With dusk came an almighty thunderclap, followed by hail, snow and finally a persistent cold rain. Lightning silhouetted the mountains, and by daybreak tent and grasslands were awash. I decided we wouldn’t be going anywhere that day, and went back to sleep.

I woke again at eight o’clock to find a miracle had happened. The rain had stopped and the sun was shining! Duojie and Busrr sized up the situation and reckoned we should set off for the source. The family rounded up their animals and came back with the news that no fewer than seven of their sheep had been killed by wolves in the night. I saw one of the bodies near the tent – the whole of its abdomen had been ripped out. So much for guard dogs!

We left at 10am, and straight away began climbing steeply towards a 16,000-foot pass. The sun disappeared and the going became difficult. I had to lead the horse over several bogs where the combined weight of horse and me would have got us impossibly stuck. We crossed the pass in heavy rain and thick cloud.

Descending into the Lasagongma Valley, I should have realised that Duojie and Busrr were leading me north towards a right-bank tributary rather than east up the main stream. “I'm sure this isn't the Lasagongma,” I wailed. “Yes it is!” they shouted back. We passed a couple of boulders with painted inscriptions in Chinese saying ‘Welcome to the source of the Mekong’, but I still wasn’t convinced. At the last patch of grass we left the horses and started walking. As the valley curved round to the west I became more and more agitated, till at last we came out of the cloud and I could see where we had gone wrong. “This isn't the Lasagongma,” I insisted again.

I thought 17,000 feet wasn’t a good altitude to have an argument, so stomped off upstream instead. It was still another 1,000 feet to where the stream emerged from the snowfield that covers Jifu Shan, but I’d come to the conclusion that it was too late in the day to get to the true source, so any old source would have to do. I was gasping – I’d never have managed the climb if I hadn’t been so angry! As I gained altitude the true source started tantalizing me across the intervening ridge. I slithered about in the snow taking photographs, then went back to join Duojie and Busrr who had already begun walking down.

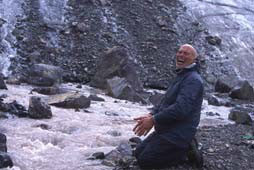

I don’t know if I’d overplayed the cross client, but back at the horses Duojie suddenly said ?Would you like to go round to the other valley?? The route turned out to be much easier than I expected, and within an hour and a half we were standing on the glacier above the proper source. I was ecstatic!

It was now a race against failing light. Not even the locals ride across boggy grasslands at night. After a manic photo-session and ritual dowsing in the ice-cold water, we set off at 6pm by a different route that Busrr knew. Luckily we were a lightweight party, having left the tents, bedding and cooking equipment at the previous night’s camp. But would we be able to find that camp in the dark? We trotted and then galloped first eastwards, then southwards, and finally followed Busrr’s pointing finger directly into the setting sun. Unbelievably, I could see that we had made a complete circumnavigation of the Guosongmucha massif in not much more than ten hours.

Darkness enveloped us and still we hurried on. No-one spoke now – we were all transfixed by the thought of the camp and the warmth of its yak-dung stove. A deer leaped across our path. We pushed on in alternate bouts of trotting and galloping, and the punishment on my bottom brought tears to my eyes. (I’m not a good horse-rider as you’ll have gathered.)

Finally out of the gloom I made out the shape of a nomads’ tent. A whiff of smoke met my nostrils. Busrr cried out, and figures appeared silhouetted in the tent’s doorway. We’d arrived. My watch said exactly midnight.

After a splendid night’s sleep our party bade farewell and continued at a more sedate pace. The sun shone serenely and the riding was easy (apart from my bruised bottom). But the Mekong headwaters weren’t going to give me up as simply as that. We reached Busrr’s family’s camp to find that Duojie’s jeep had a flat tyre.

It wasn’t so much a flat tyre as a slow puncture. “No problem,” said Duojie, “Chinese tyres have slow punctures built-in.”

Next morning we got his spare tyre installed, said goodbye to Busrr’s family and set off southeastwards. The river that had nearly defeated us earlier was flowing much higher now, but Duojie was in bullish mood. He drove straight into it. The water came over the bonnet and swished wildly around our legs, but amazingly the jeep didn’t falter.

Towards the top of the next pass we had another puncture. “No problem,” said Duojie, fishing out his second spare tyre. But it was completely flat. What do you do in the middle of nowhere with two flat tyres? You walk. At least that’s what Duojie set off to do. I tried to stop him – a storm was brewing and the nearest help was at Zaqing 50 miles away – but all to no avail. As soon as he left the storm broke. Lightning crackled around the jeep. I was cosy inside but I was sure Duojie was going to die. I should have known better. An hour later two jeeps appeared over the horizon, got steadily larger, and finally swished to a halt in the mud beside me. Out of one climbed Duojie with a big grin on his face – he’d negotiated to swap his deflated spare tyre with one of their good ones.

We arrived in Zaduo the following morning, after the toughest but most rewarding bit of exploring that I’ve ever done. I can’t begin to express my admiration for Duojie and Busrr, and my gratitude that they were willing to take on a complete novice in the saddle. As a footnote, the Mekong’s source was only identified by the Chinese state mapping authority in 1999, after an Anglo-French team led by Michel Peissel claimed to have found it 55 miles to the southwest. The true source has been reached by the Chinese, Japanese, Americans, Norwegians, Finns, and now a Brit.

For any of you interested in details, five

sources have been claimed for the Mekong over the past ten years.

Having listened to Duojie and Busrr’s discussions with our

nomad hosts and others, I’m pretty sure that the Chinese

cartographers, in declaring the true source to be the glacier

on the north face of Guosongmucha in 1999, wrongly named the stream

issuing from this glacier as the Lasagongma. This was reported

by Xinhua, the

national news agency, on 9th November of that year, and resulted

in at least one expedition from Yunnan being guided up the real

Lasagongma stream which rises at just over 18,000 feet on the

east face of Jifu Shan. This was the team that left the painted

inscriptions on the boulders, before descending in poor weather.

The true source lies at 17,140 feet and the stream issuing

from it is called the Lasawuma.