“Why on earth would you want to stay for a month?” asked the immigration officer in the Eritrean capital Asmara. It was a question I’ve grown used to since arriving in this forgotten part of the Horn of Africa.

How difficult life can be for Eritreans! Half her young men are in the army, and the other half are struggling to make a living. Electricity and water are a real luxury, leaving some people trapped in a circle of poverty shocking even by African standards. (Click any photo to enlarge; click again to enlarge further.)

Despite it all, I’ve noticed that Eritreans do laugh and smile a lot. Most are well dressed, and many are well educated. Crime hardly exists. Houses may be basic, but they’re always kept clean.

I found the market halls more encouraging, with plenty of well-stocked stalls. In the surrounding streets people had laid out an astonishing range of things for sale on the ground, from vegetables to car springs to old cassette tapes.

When the Italians came to rule the country 130 years ago, they were so taken by Asmara’s perfect mountain climate that they decided this was the place to show off the work of their finest architects. The early buildings were simple and classical; then Mussolini set about transforming it into the Art Deco capital of his pipedream East African empire. So amazingly, some of the world’s best interwar buildings can be found here, crumbling away under the African sun.

It’s Saturday night in the town of Keren. No power, so no streetlights. With its sandy roads it reminds me very much of Timbuktu, but here half the people are Muslim and half Catholic so the atmosphere is slightly different. Strolling the streets in the early evening has been a joy. Neighbours catch up with neighbours, and the corner shops are busy under assorted lamps and generators.

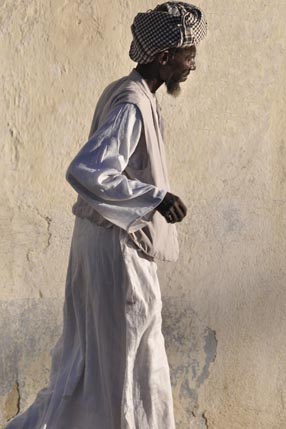

It’s hard to describe how different this is from cosmopolitan Asmara. Boys kick and shoo goats; cows amble about; and farmers in white robes lead camels bringing in produce from the countryside. I’m staying in a tiny pension with water from a well, where the call of the nearby muezzin is a familiar and comforting sound. And of course there’s no television anywhere at all. Paradise!

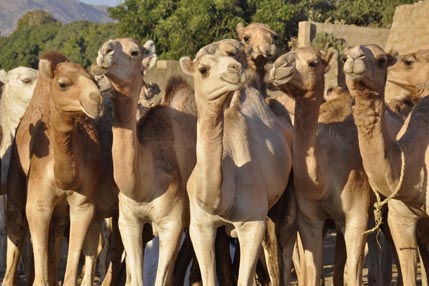

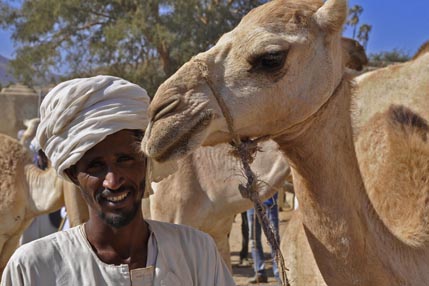

I came here for the Monday morning camel market, and wasn’t disappointed. Two hundred of them were gurgling and snorting in a compound on the edge of town. Watching and listening to the traders, I found out how to tell a strong healthy camel from a runt.

Then it was down to the Red Sea coast and the port of Massawa, built by the Ottomans and later an Egyptian and Italian stronghold. It’s suffered terribly from earthquakes over the years, not to mention bombing during the war with Ethiopia.

Queen Victoria’s Abyssinian expedition disembarked at a stretch of shoreline called Mulkatto, not far south of here. All that’s left of the port and railway are a little stone pier and a single rail, rusted almost beyond recognition.

As the sun rose on midwinter’s morning, I stepped with my guide from the village of Zula onto the remains of that historic pier. Before me was a scene unchanged since Lord Napier’s time. To the east, tidal mudflats. And to the west the desert that would lead me up into the Abyssinian highlands.

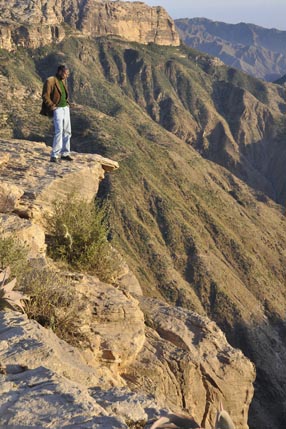

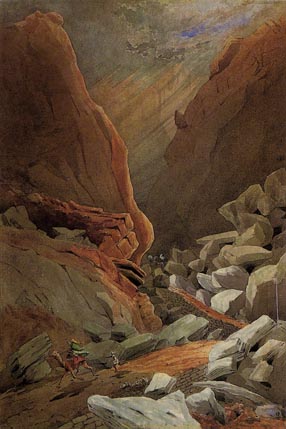

The expedition artist, Frank James, painted a vivid record of what he called the Devil’s Staircase, which today is known as the Camel Road. Looking down on it, I was left speechless by the enormity of the escarpment they had to climb. His watercolour couldn’t possibly do it justice.

My predecessors made camp beyond the top of the pass at a place called Senafe. Today it’s a dusty border town, home to displaced people and frontier guards. In the no-man’s-land to the south I heard gunfire, but hopefully they were just practising.

It’s been a thrilling start to the trip, and in January I’ll fly to Ethiopia and come back to this closed border to begin the next stage. I’ll write again soon.