You couldn’t make this story up.

In March 1868 some 13,000 British and Indian soldiers, 26,000 camp followers, and more than 40,000 animals including 44 elephants, were strung out along the 400-mile route from the Red Sea. Emperor Tewodros had moved his hostages to a formidable natural fortress called Magdala, and the force faced climbs and descents of thousands of feet as they picked their way across the precipices and ravines.

These are paths made for visiting your neighbours, not for walking hundreds of miles. Some of the drops were lethal and I was incredibly lucky not to fall over them. Local people and donkeys were carrying much heavier loads than mine. (Click any photo to enlarge; click again to enlarge further.)

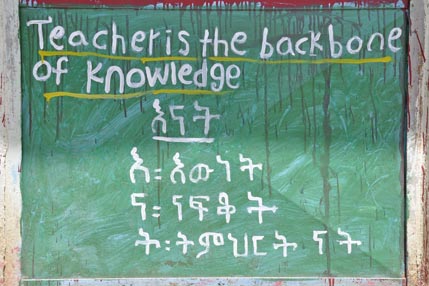

I’m glad to say life in the countryside has improved a bit since Lord Napier’s time. Schools and roads have made a real difference, but things are still tough for many people.

Two vital things are water and cereals. Some lucky villagers have a well with a modern hand pump. Others rely on natural waterholes which, as my companion Gebru and I found to our cost, often dry up.

Cereals are the number one crop all over the Ethiopian highlands. They’re a special type called ‘tef’, essential for making the injera that everyone loves so much. First a lot of sifting and separating goes on; then it has to be milled into flour, so I often met long lines of people and donkeys carrying bulging sacks towards the flour mills. Each sack is carefully weighed and paid for by the kilo, before the flour is carried all the way home again.

After that of course there’s fodder and bedding for the animals.

Weekly markets take place on the bare hillside.

Finally we had just two more ravines to cross.

The 1868 campaign didn’t end happily. After a fierce battle, Tewodros drove hundreds of native prisoners over a cliff and then shot himself. But the European hostages were all successfully rescued, and his prize mortar ‘Sebastopol’ is now proudly displayed nearby.

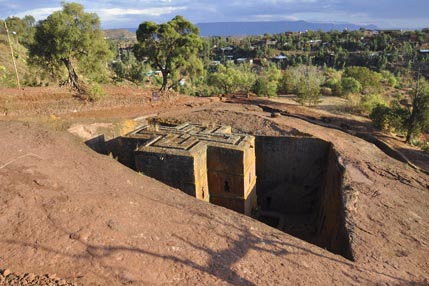

I finished my walk at the beginning of April, but couldn’t come home without seeing the world-famous churches of Lalibela.

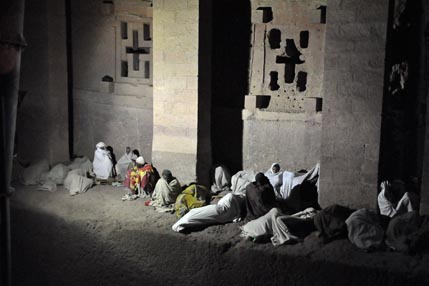

It was Ethiopia’s Easter – a week later than ours – and everyone in Lalibela was looking forward to their ritual feasts of chicken and goat.

But first they crammed into the town’s eleven churches for an overnight candle-lit vigil.

The walk was one of the most difficult I’ve ever done, despite having Gebru with me who was a sheer delight. And the rest of the trip? Well spending a month in Eritrea – which has isolated itself from its neighbours and gets hardly any visitors – was a real privilege and eye-opener (Update 1). As for Ethiopians, they’re boisterous and charming and whatever the frustrations they never complain. In both countries, ox-ploughs and mud-and-thatch houses are the norm over wide areas, and these would have been familiar to the soldiers who marched through the Abyssinian highlands all those years ago. But towns like Gonder and Lalibela are a joyous mix of ancient and new. If you haven’t been to this part of the Horn of Africa, you’re missing a treat.