Not for nothing do they call the Simien Mountains the Roof of Africa. They aren’t exactly mountains – more a sloping plateau, deeply dissected by river valleys, which rises northwards to a stunning 6,000-foot escarpment. Part of its drama is because the escarpment is a series of jagged edges, the peaks being where ridges have been sliced through by vertical cliffs.

Once upon a time the region was intensely volcanic, so there are plenty of ‘sugar-loaf’ peaks as well. (Click any photo to enlarge; click again to enlarge further.)

But best of all were the gelada monkeys! They’re often wrongly called baboons, and went about in troops of a hundred or so, grazing on grass roots.

I was surprised to find them quite inquisitive – one nearly walked over my boots – and more than happy to pose for photos.

You could almost imagine them chatting to each other. In front of me, one picked up a rubber band, turned it over in his paw, bit on it, then handed it to his mate saying, “What do you think of this?” The mate did the same, then flung it contemptuously aside. “Just rubbish,” she said.

Other wildlife kept its distance, but I was excited to spot a young walia ibex, and a rock hyrax which the mountain people rather unkindly call a rat.

Having spent a month in Eritrea, I was terrifically privileged to be invited to one of the refugee camps that Ethiopia has set up near the border. Unbelievably, one in ten of Eritrea’s population has fled the country in recent years. The Adi-Harush camp has seen 56,000 of them come and go since 2010.

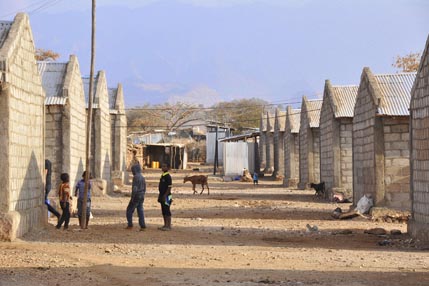

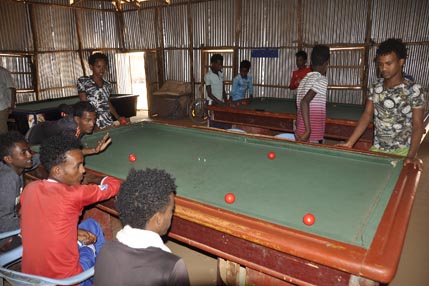

Remembering camps I’d seen in other countries, I expected to find flimsy makeshift canvas shelters, but quickly had to revise my thoughts. At Adi-Harush neat rows of breezeblock houses, each for two families, stretch into the distance. There’s a medical centre, a primary school, a church, mosque, communal kitchen, market hall, hairdressing salon, football pitches and even a pool hall and cinema.

Sixty or so new refugees arrive every day, and they’re taken to a UN-funded reception centre for health checks. Many are unaccompanied children, and all will be suffering from malnutrition, including mothers with babies and sometimes pregnant women. The border crossing is highly dangerous and some are traumatised, so the camp staff and fellow Eritreans have to work together to help them recover. After 45 days, those with relatives or friends who can support them leave the camp, and some settle in Ethiopia. But lots of others make their way through Sudan to Libya in a desperate effort to reach Europe. I shudder to think that some of the gentle people I met in the camp will perish on that horrible journey.

The sense of spirit and hope in Adi-Harush was inspiring, but it doesn’t filter down to everyone. Some refugees simply have nowhere to go. Afewerki Tekeste, their elected leader, has lived in the camp now for six years. “It’s just a matter of surviving,” he told me.

Later this month I’ll be back on the route of Queen Victoria’s expedition, and will have some catching up to do. I’ll write again soon.