Tuaregs

Tuaregs

Tuaregs

TuaregsImagine you’ve just had a brainwave. Your people’s rebellion against the Malian Government has ended with a symbolic burning of arms, and to help the reconciliation you want to organise a festival to celebrate the music of all sides involved. Where would you hold it? A place called Essakane flashes through your mind. It’s an oasis of pristine white sand dunes surrounded by several dozen miles of uninhabited desert. It has no buildings, no water, no electricity and no roads. You’d dismiss it as a pipedream, yes?

Not if you were a man called Manny Ansar. In 2001 and 2002 he started things going in compromise locations, but from 2003 onwards, with the support of Ali Farka Touré and one-time Led Zeppelin vocalist Robert Plant, the embryonic desert gathering established itself in Essakane as the ‘Festival au Désert’ – Mali’s answer to Glastonbury.

So it was that on 13th January 2006, several thousand Malians and some 700 foreigners ploughed their way from Timbuktu through 40 miles of sand and scrub to where the action was about to begin. They came in pickups, in jeeps, in Land Rovers, on lorries, on motorbikes, on camels and on foot. Some got stuck in the sand or broke down and had to be rescued by others. Meanwhile at Essakane a stage was built, a generator coaxed into action and makeshift restaurants and water points set up. Finally, as the sun went down and a full moon rose to bathe the dunes in a ghostly light, the first chords struck up to begin three days and nights of inspirational music by 30 bands from three continents.

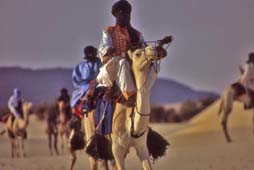

For me the mix of people was almost as amazing as the music. Turbanned Moors straight in from the desert mingled with tall, black-skinned people from the West African coast. Tuareg nomads galloped through the crowds on their camels. Knots of Europeans and Americans stood around looking nonplussed. Most of the musicians were Malian of course, though they also came from Niger, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Guinea and South Africa, and on the second night were joined by the American blues guitarist Markus James and an Irish folk group called Aiestar. Inevitably the music was mostly African rock, but it was good to see some of the artists also playing more traditional instruments such as the Songhai njarka, a single-stringed violin that has been sounding out across the Sahara for a thousand years.

The magic was all too quickly over, and

back in Timbuktu the surge of visitors dissipated and the streets

returned to their fly-blown selves. But I had work to do. Four

hundred and fifty miles to the north the salt mines of Taoudenni

were waiting. It was time to get ready for the big trip. I’d

already found a camel-owner, a Moor called Adei Ould Ashehr, and

we’d agreed a price for providing me with three camels, an

Arabic-speaking guide and a return to Timbuktu by four-wheel-drive

pickup. Our provisions would consist mostly of rice, peanuts and

dates, washed down with hundreds of tiny glasses of sweet green

tea. Adei Ould Ashehr insisted I dress as a desert nomad “so

as not to frighten the camels”, so in the Petit Marché

I found a machinist who measured me up and delivered a three-piece

robe in traditional Saharan royal blue, set off by a white turban

to swaddle my head. There was now no time to lose; the Harmattan

was starting to raise the dust and by February the desert would

be sizzling. I had my head shaved in a barber’s shack, made

a final foray to the market for a last-minute roll of loopaper,

and was ready to go.