Since the last update I’ve been humbled by people’s generosity, and appalled by tragedies on a grand scale. But first, what could be more stylish than The Nutcracker at Odessa’s glittering Opera House – my first ever ballet, complete with pancake tutus!

Then it was on to the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, and from there north to Chernobyl, still a scene of inconceivable devastation almost 30 years after Reactor No. 4 blew up. (Click any photo to enlarge.)

At virtually no notice, 53,000 people were evacuated. They never returned. Although safe for a day visit, the 30-kilometre exclusion zone won’t be fit for human habitation for another 20,000 years.

A tragedy of a different kind is being played out in Ukraine’s far east, where Russian separatists are in a life-and-death struggle with government forces supported by armed mercenaries.

In Dnipro (then called Dnipropetrovsk or ‘Petrovsky’s city on the Dnieper’) I met Evgenij Urchenko (above right), just back from visiting his wife and baby daughter across the front line. His eyes welled with tears as he told me about the booms and thuds of the shelling, “some far away, a few horribly close”.

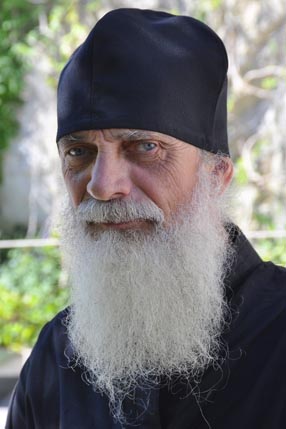

On the same day a friend called Dima told me of his harrowing 15-month tour of the separatist-controlled area as a government mercenary. Here he is below, then and now.

As we were chatting, another of my new-found friends, Roma Nazarchuk (above right), burst out angrily, “Why did our government give Crimea to Russia on a plate? They didn’t even fire a single shot!” I’d heard this story several times already, spoken with varying degrees of bafflement and fury. It seemed time to go to Crimea and find out.

The peninsula of Crimea is slightly bigger than Wales. Its backbone of craggy limestone hills was home to 300,000 Tatars, until Stalin deported them to Central Asia in the 1940s. In 1954 Mr Krushchev presented it to Ukraine, and in 2014 Mr Putin took it back again.

During the Cold War, the Soviets carved a vast nuclear bunker into a hillside at Balaklava. Today it’s a popular tourist attraction. You can stroll through miles of cold corridors, marvel at the cavernous submarine dock, and inspect a genuine nuclear warhead (disarmed, I think).

It’s been fascinating to hear people’s different views on Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Many are enthusiastic, but for Ukrainians and returning Tatars the situation is more complicated. They can’t get Russian passports, and some families have been tragically split up.

Edaye Muratova, a Tatar who runs a stall in Yalta’s central market, told me “We’re Ukrainian. Always have been, always will be. We don’t like being part of Russia.”

But for better or worse, Crimea is now firmly under Russian control. The carefree Muscovites enjoying Yalta’s sights may seem the same as ever, but that’s because in nearby Sevastopol the Black Sea Fleet is on standby.